Collateral Damage

Monetary leaders have created new risks by eliminating old ones

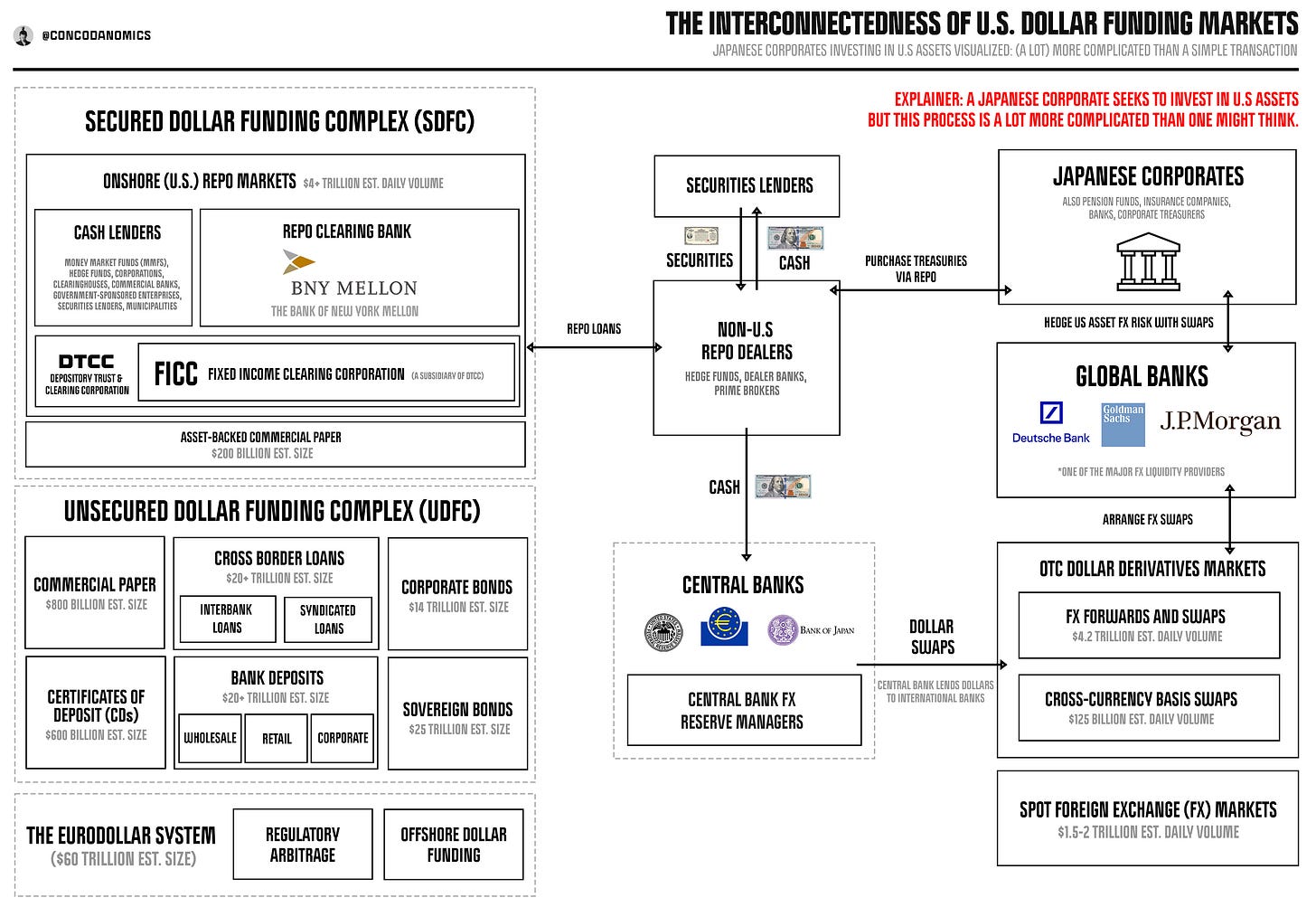

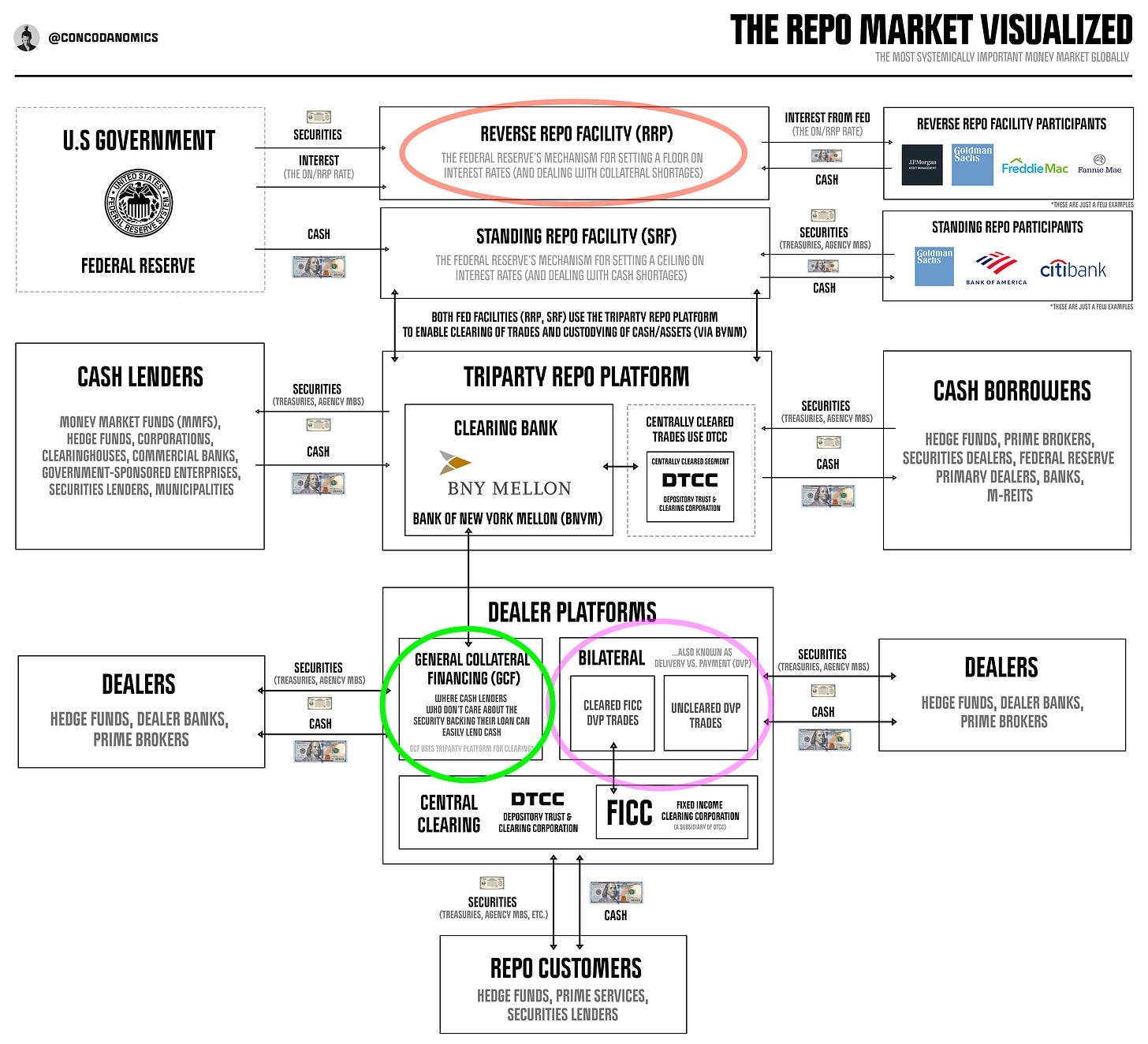

Whispers of a “collateral shortage”, a lack of safe assets that form the major daisy chains of the global monetary system, have been circling all over financial and social media. But in reality, we’re far from it. The U.S. empire has embarked on a debt-issuance bonanza these past few years, and the financial behemoths have eaten all they can chew. What’s more, a reworked innovation of the Fed, a reverse repo facility by the name of “RRP”, has provided practically infinite amounts of safe assets for systemically important entities to consume, enough to ward off any major plumbing upheaval.

The recent insatiable bid for ultra-short-term Treasury paper, which drove the speculation, is instead the frontrunning of a debt ceiling fiasco, a drama that’s about to unfold.

This is yet another classic case of enormous demand for t-bills (Treasuries with a one-year expiry or less) that mature before an impending debt ceiling drama hits Bloomberg terminals. The U.S. empire — as a whole at least — is not going to let itself default on its debts, yet investors always prefer the assurance of repayment, plus the comfort of not having to deal with another debt ceiling debacle. The enormous amount of liquidity stored in global money pools has found its way mostly into short-term Treasuries, over a sea of other alternatives in the global dollar funding complex.

Subsequently, we’ve seen rates on 1-month bills plunge over the last few weeks and below every other short-term investment, from GCF repo (green, below) to the Fed’s O/N RRP facility (red, below).

Another one of those short-term investments is bilateral repo (pink, above), resting alongside GCF (general collateral financing). Bilateral repos act as quasi-bills, providing similar intraday liquidity. Unlike the Fed’s RRP facility which returns overnight funds at 3:30 pm, cash from a bilateral repo is returned at 8:30 am, with the added option to exercise later on at any time during business hours — thereby mimicking intraday liquidity of bills.

When the supply of bills dries up, the bilateral repo market acts as a sponge, absorbing excess cash that would otherwise make it into the t-bill market. This is what we’ve witnessed just recently in Conks' U.S. Money Market complex.