Quantitative Teasing

the response to the latest banking panic was a stopgap, not a full-blown pivot. Say hello to Quantitative Teasing™

The Great Financial Tightening has thrown the global monetary system into disarray, prompting large interventions by financial leaders. Markets perceived their response as a pivot, but it was merely a stopgap. Another “hard landing” now awaits us.

Ever since the great financial crisis in 2008, the system has been sculpted not by sound pre-planning of monetary policy, but by a series of experiments created during a myriad of crises. The response to the latest banking panic was just a taster of the Fed’s financial alchemy. Only four years ago in September 2019, the most relevant episode to today’s fiasco hit our screens. The repo market, where parties borrow short-term cash against collateral (usually Treasuries or state-issued mortgage-backed securities) broke down in spectacular fashion.

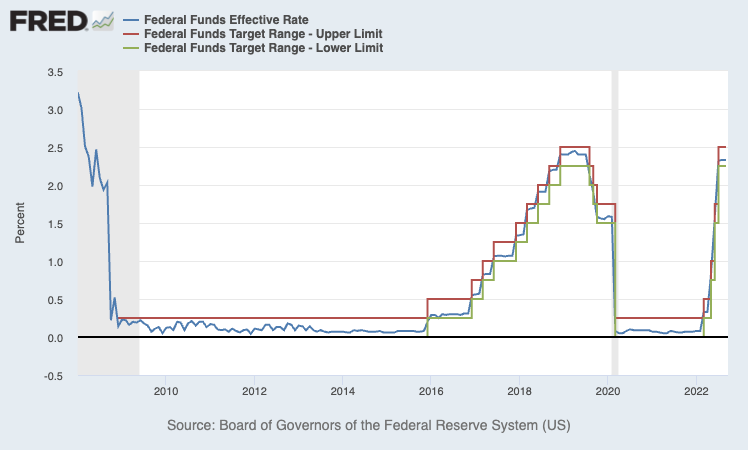

At the start of 2019, the rate earned for lending in repo, SOFR (the Secured Overnight Indexed Rate), began to rise above the interest rate banks earned on their reserves: IOER (Interest on Excess Reserves) — now called IORB (Interest on Reserve Balances). The banks piled into the repo market, fast becoming prominent lenders in the most systemically important market globally.

Then in September, the private sector sent a large number of corporate tax payments to the American government, sucking liquidity from the banking system into the U.S. Treasury’s coffers. Meanwhile, banks, now major lenders in repo, had to also absorb a large issuance of Treasuries. What could go wrong?

A lot, it seemed. Only a day later, the Fed’s primary interest rate, Federal Funds, suddenly shot above its intended target range. At the same time, SOFR indicated that rates in repo had soared to over a whopping 5%. The Fed saw no other choice but to act swiftly and intervene.

Facing a crisis, while unsure of a genuine cause, the Fed initiated yet another round of quantitative easing (QE), plus a series of overnight and “term” repos (jargon for loans extended over a fixed period of time) to push the Fed Funds rate back within its target range. They succeeded.

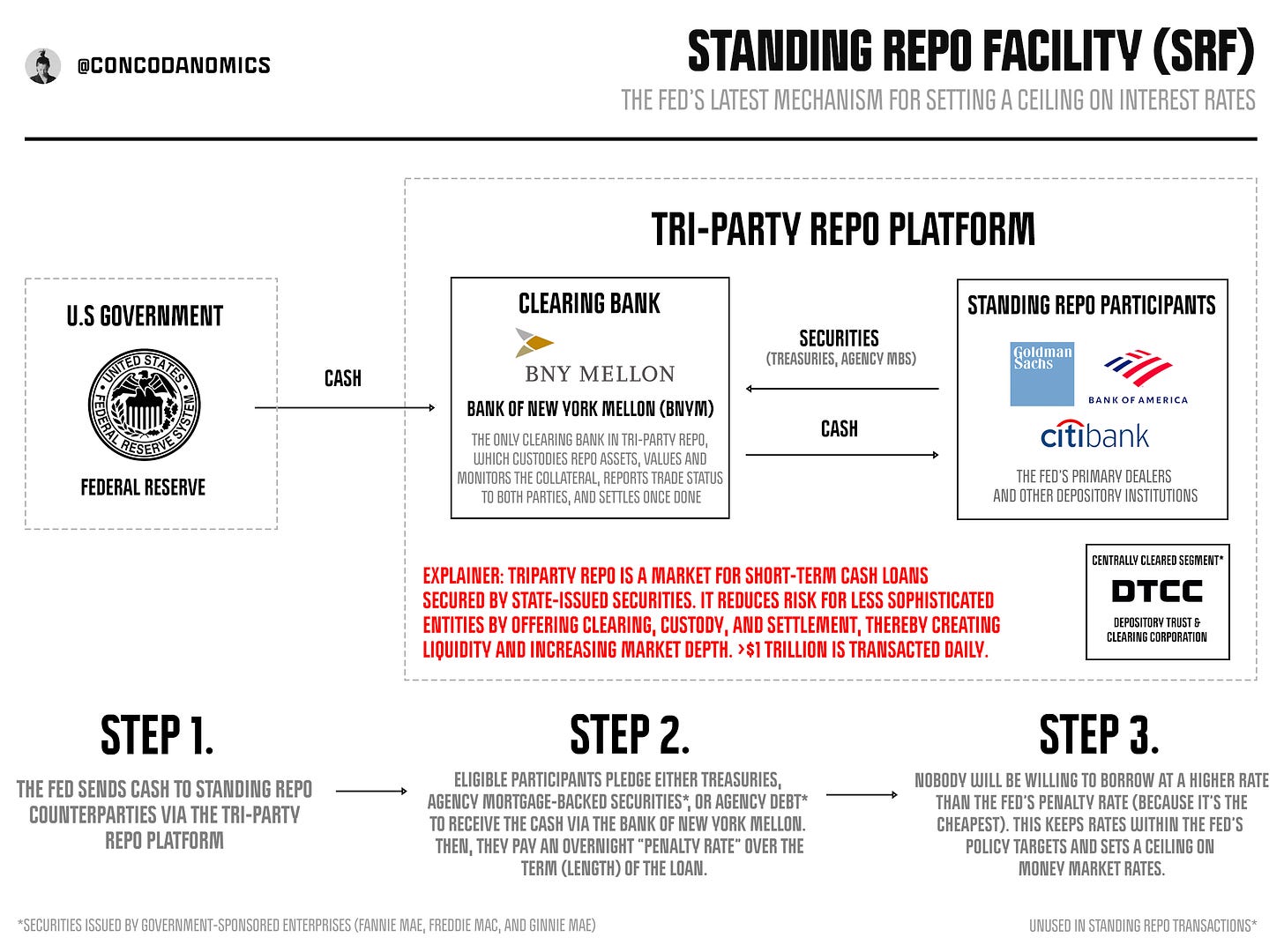

The Fed jamming $53 billion into the system caused a rapid decline in money market rates. By simply offering cash to primary dealers — a group of banks and securities firms — at the cheapest price possible, the Fed stemmed the crisis and thwarted further contagion. These actions went on to become the basis for a “temporary” — meaning permanent — tool to prevent recurrences: the Standing Repo Facility, or SRF.

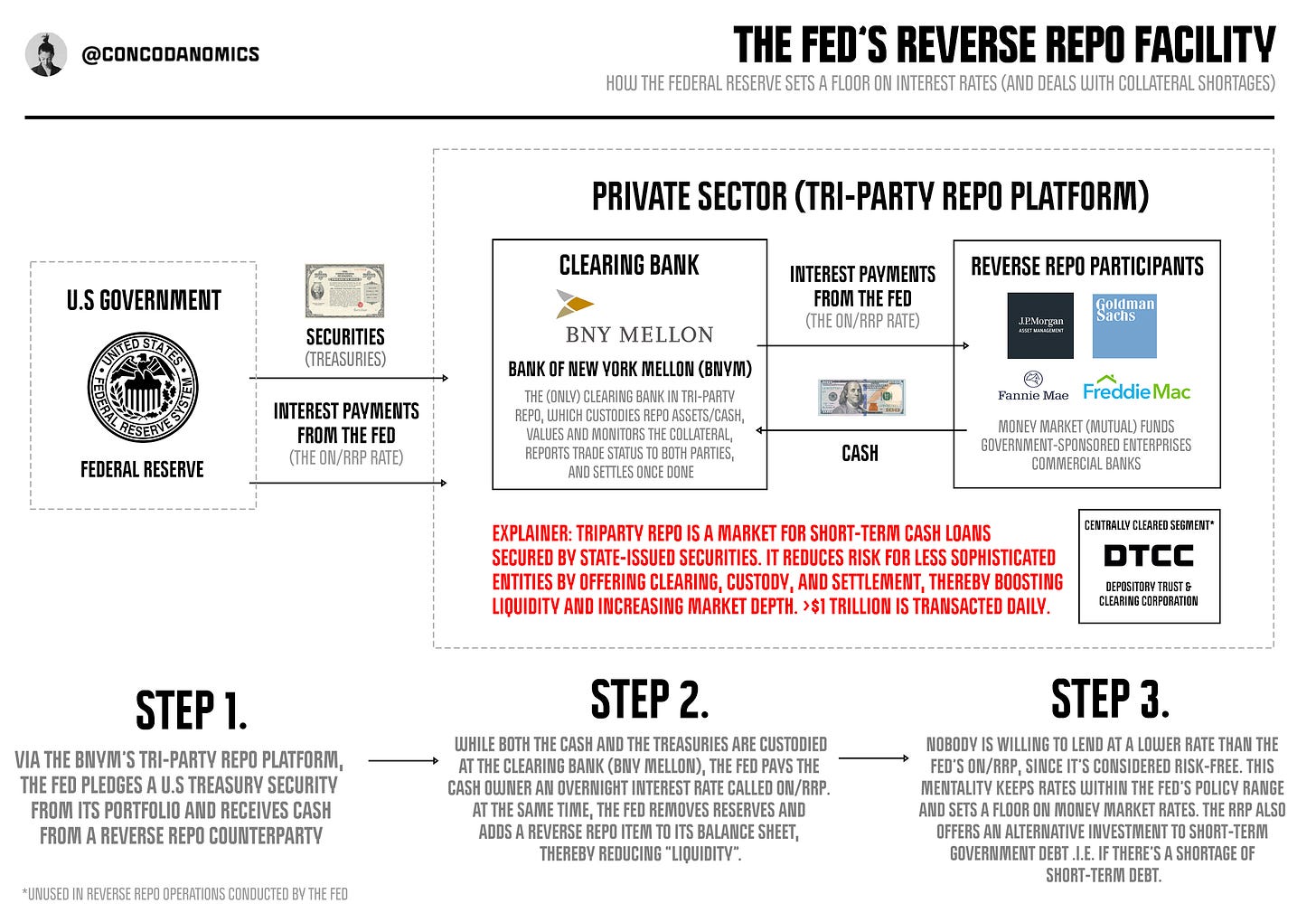

The SRF would join forces with another creation of the Fed: the Reserve Repo Facility (RRP) introduced in 2013, which has gained much attention lately. While the SRF was meant to prevent rates from rising above the Fed’s target range, the RRP would defend the floor by offering an optimal risk-free rate, out-competing lower private sector alternatives.

Markets, however, always find a way to disobey the Fed. Back in late-2015, as a Credit Suisse report illustrated, the market not only drove Treasury yields below the Fed’s target range but into negative territory. The RRP’s floor grew more than “leaky”.

After the floor was breached numerous times, the Fed nevertheless stated it would phase out the RRP after it was “no longer needed” to stop rates from misbehaving. But markets are complex systems. Today, the RRP not only remains in operation but holds over $2.2 trillion in outstanding transactions.

Since the 2019 repo blowup, the Fed had assembled all the tools necessary to keep money markets rates firmly within its target range. From then on, the potential for further mishaps, and fresh alchemy from monetary leaders, lay elsewhere. Then, the bank run hysteria, a mix of miscommunication, inexperience, and excess, emerged out of nowhere. A run on Silicon Valley Bank led to a run on regional banks, which only swift intervention could prevent. It was time for monetary alchemists to fire up the lab once again…