Despite the Federal Reserve’s easing programs persisting, dollar strength has begun to accelerate once again. But as liquidity subsequently drains, the world’s response will not be to de-dollarize but to seek more dollars. The U.S. central bank’s global swap network is set to expand.

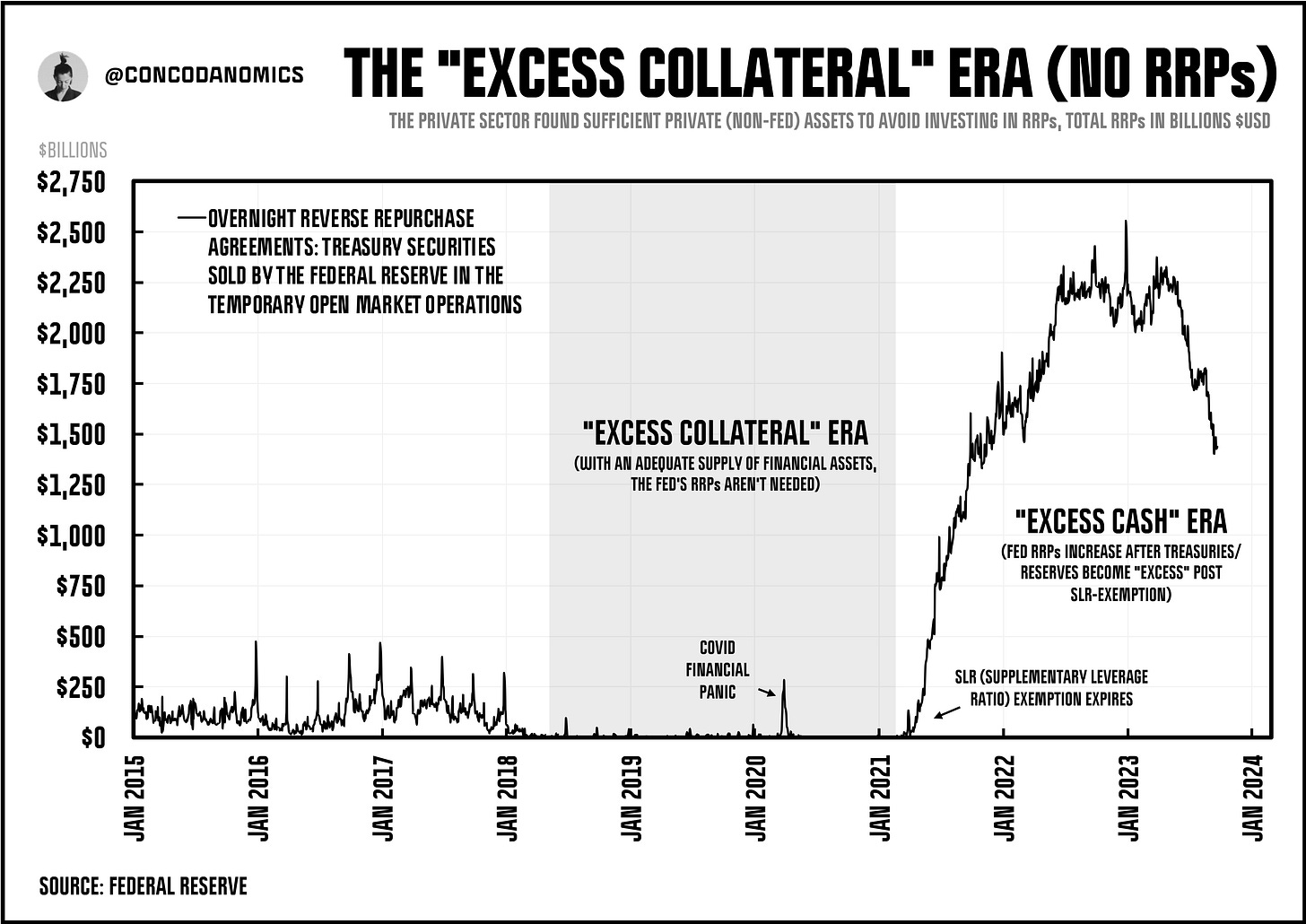

Back in 2019, before the Fed unleashed trillions of dollars in liquidity to stem COVID fears, global markets had entered a lengthy “excess collateral” era. The Fed’s RRP (reverse repo) facility, a shock absorber for excess cash and the defacto measure of surplus liquidity, lay empty. Almost every dollar was being deployed by private sector entities into trades that did not alter the Fed’s balance sheet, from repos funding leveraged Treasury investors to Eurodollar arbitrage by New York branches of foreign banks. Soon, however, a relatively unknown trade was not only about to upend the excess collateral era but also the illusion of financial stability in the Fed’s post-crisis system.

Midway through September 2019 on the 17th, a funding squeeze caused money market rates to skyrocket. The Fed’s SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate), a measure of the average cost to borrow cash secured against U.S. Treasuries, showed repo rates spiking above a whopping 5%. Meanwhile, in a frantic search for other sources of dollar funding, financial entities had even begun tapping the once-lifeless interbank funding market, sending the Fed Funds rate (EFFR) above the U.S. central bank’s upper limit of its target range.

The Fed responded with a Standing Repo Facility, and shortly after, the “repocalypse” subsided. But the central bank’s bottomless interventions were no longer the major astonishment. The system was not as stable as monetary leaders and prominent financial players had assumed. It was soon revealed that most market players knew on the day of the repocalypse that liquidity was about to grow scarcer than usual. Days before, most were aware that corporations would be pulling large sums of cash from MMFs (money market funds) to fund quarterly tax payments, while the U.S. Treasury would be issuing additional government securities into an increasingly illiquid market. Both would pull liquidity — in the form of reserves — from the banking system into the TGA, the government’s bank account housed inside the Federal Reserve System.

At the same time, those same financial actors had been assigning large quantities of reserves to trades in the repo market. While dealers increased their repo borrowing to a point where their inventories — and thus their balance sheets — had reached near capacity, lending in repo became so profitable that banks made more deploying reserves into repos than depositing these at the Fed and earning IOER (interest on excess reserves). These decisions were also made in the depths of the Fed’s first official QT (quantitative tightening) program, which aimed to drain billions in reserves from the financial system every month. All in all, the late-2019 repo market had become a ticking timebomb.

Yet in the aftermath and throughout the repocalypse, another market undergoing mild stress had barely been covered in the media: the $4 trillion-a-day FX swap market. As smaller participants failed to locate funding both in repo and the interbank markets, the rate to borrow dollars secured against foreign currencies spiked, though only slightly. But it was merely a few months after the repo spike faded from mainstream circles that we’d not only discover what real stress in the FX swap market looked like. The world would also come to acknowledge the Fed’s global dollar swap network as the FX swap market’s sole rescue mechanism in times of crisis. The Covid financial panic had emerged, and with it came swap lines.