The Reverse Repo Endgame

as the RRP hits zero, the "repo hierarchy" is about to be activated

After the Fed’s largest liquidity injection on record, the “excess cash” era is coming to an end. Trillions of reserves once trapped in the Fed’s RRP (reverse repo) facility have been released to replenish the U.S. government’s bank account and fund QT (quantitative tightening). As the RRP balance reaches zero, the dynamics in the repo market are about to transform. The return to an “excess collateral” era awaits us.

In April 2021, the Federal Reserve began unwinding measures that enabled its largest monetary expansion on record. During the COVID-19 panic, the Fed allowed banks to absorb vast flows from QE (quantitative easing) by exempting reserves and Treasuries from its SLR (Supplementary Leverage Ratio) — a constraint that requires banks to hold a minimum amount of capital against all assets, no matter how risky or safe. But by early 2021, the Fed decided to let this exemption expire. The banks, meanwhile, had absorbed so many low-yielding reserves that the SLR began to threaten their bottom line. Making room for more profitable operations, banks initiated a “great shedding”, pushing deposits (and thus reserves) off their balance sheets. This money could only end up in one place: the Fed’s RRP, the sole shock absorber for excess liquidity. The multi-trillion-dollar RRP buildup had commenced.

Around the same time in 2021, the U.S. Treasury ended its mammoth issuance of Treasury bills used to fund emergency COVID operations. From a peak of $5 trillion outstanding, the value of t-bills in circulation fell by hundreds of billions each month, reducing the supply of safe assets significantly. MMFs (money market funds), which had developed a taste for short-term government debt, were forced to turn to the Fed’s RRPs as an alternative investment. These money funds were also the recipients of the banks’ deposit exodus, further increasing their need to invest in RRPs. As the inflows continued into 2022, the volatility of the largest bond market drawdown in recent history encouraged even greater demand for RRPs while also preventing outflows. If that wasn’t enough, soon after, retail and institutional investors began moving money into MMFs to chase superior yield and avoid the SVB-induced banking panic. By the start of 2023, the RRP balance was housing a whopping $2.5 trillion in excess liquidity.

After the resolution of the latest debt ceiling debacle in June 2023, however, the U.S. Treasury once again issued a deluge of Treasuries into the market, ending the safe asset deficit. The RRP balance had finally peaked, initiating the RRP drain.

As heavy issuance made yields on government debt more attractive than the Fed’s RRP, the primary RRP drainers, MMFs, used cash stored in the Fed’s facility to fund a sea of Treasury purchases. Banks also likely contributed by attracting depositors they once pushed out, restocking dwindling reserve balances lost from QT and MMF outflows. The two other types of RRP counterparties had no reason to use the facility either. Since the Fed paid less than the rate to borrow in private repo, primary dealers would make a loss deploying cash into RRPs. Meanwhile, GSEs (government-sponsored enterprises) likely exited after finding better yields elsewhere. With every entity locating superior investments, the RRP drain had entered beast mode.

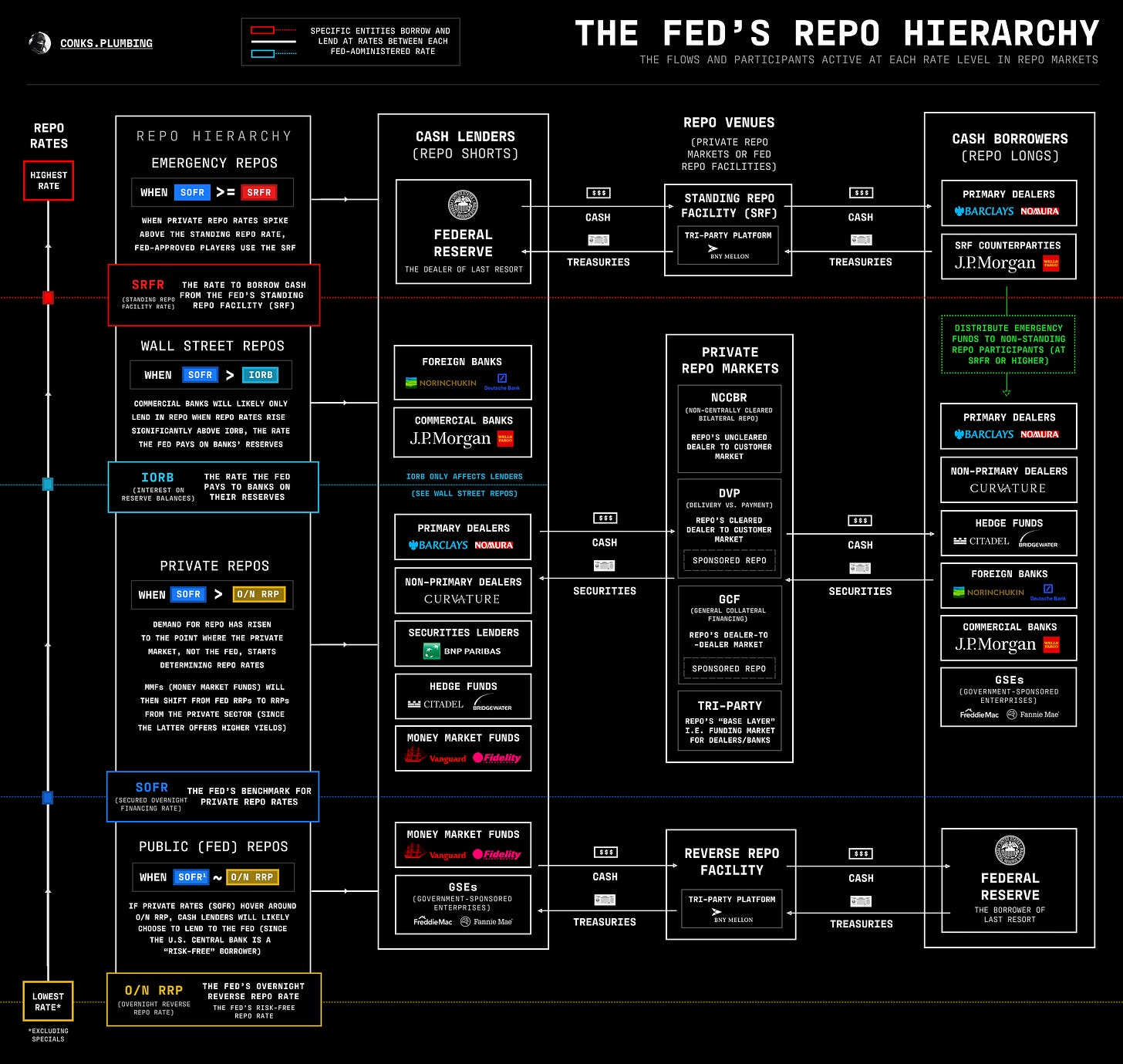

Today, the RRP balance has plunged below $800 billion and is fast approaching the zero bound. Eventually, cash available for repos will grow scarce, awakening once undead parts of the market. The upper levels of the Fed’s “repo hierarchy” will be activated, altering the status quo in the most crucial funding market globally. What does that mean in practice? It’s time to go deeper into the mechanics.