The Shadow Bank Shutdown

the origins and status quo of shadow finance

After decades of overlooking runaway financial speculation, Chinese leaders have miraculously deflated a once-giant shadow banking system without widespread turmoil. Yet as the global economy begins to stall, China’s elite may encounter a resurgence of financial alchemy in the shadows. The “Shadow Bank Shutdown” has likely reached its pinnacle.

Fifteen years ago, on 15 September 2008, America’s fourth largest investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed, revealing the most intricate network of financial instruments ever assembled. Decades of experimentation in America’s banking golden age, mostly hidden from the public eye, had risen to the surface. The U.S. shadow banking system was unveiled. The reaction to this shadow system’s exposé was one of amazement and disbelief, but it was the peak of a transition to a new type of finance, one that had been evolving since the 1970s. In contrast to the traditional banking textbooks, “market-based finance” — the intermediation of credit outside the traditional system — had not only emerged but superseded the original banking model. The subprime boom and bust was merely the byproduct of market-based finance’s first modern iteration, and as usual with nascent monetary experiments, it ended in disaster.

But unlike the origins of market-based finance, where private entities created “deposit-like” instruments (such as repos and money market funds) to evade regulatory hurdles, the origins of America’s shadow banking standard lay within government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). The FHLB (Federal Home Loan Bank) System, dubbed the second-to-last lender of last resort, was the foremost provider of “loan warehousing” — extending credit to those engaging in the securitization of mortgages. Meanwhile, similar to big banks providing “backstops” to shadow entities engaging in dubious activities, the housing GSEs (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) provided the first forms of “credit risk transfer,” much like CDS (credit default swaps) and CDOs (collateralized debt obligations). These government-sponsored entities even founded the “originate-to-distribute” model, where lenders made loans for the sole purpose of selling them on to other investors.

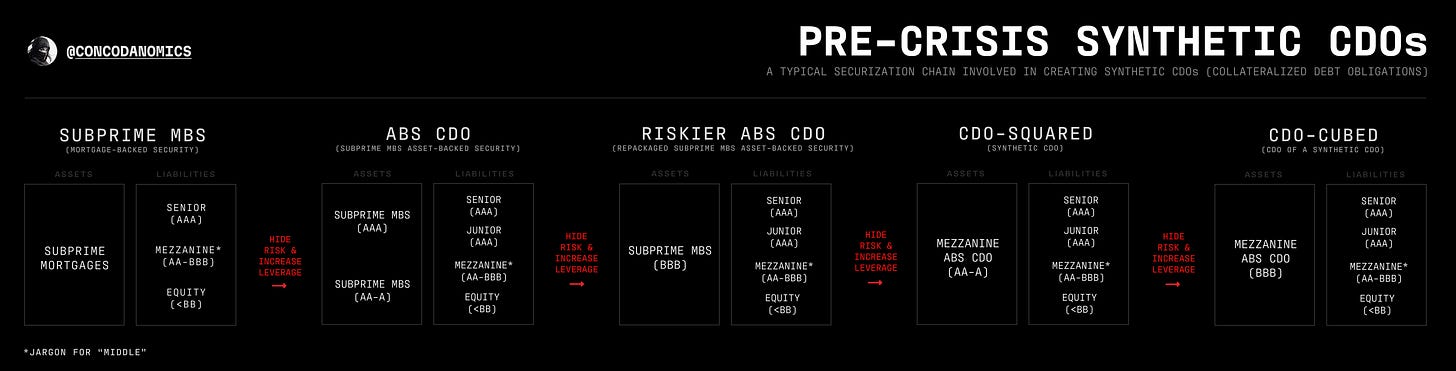

In an even more bizarre dynamic, the infamous rise of CDOs was prompted by the first draft of the Basel Framework, the regulatory banking standard active in practically every major nation. Following the late-1980s banking crises, monetary authorities enforced Basel I’s minimum capital requirements on banks, aiming to curb credit risk: the probability of loss from counterparties defaulting on loans.

Yet Wall Street swiftly found a way to game the system. By pooling mortgages into securities and “reducing risk” via CDO and CDS products, banks required less capital than traditional lending to generate similar returns. CDOs, essentially securities that yield interest from another pool of securities, were deemed to be “credit risk transfers”. Still, the pieces known as tranches that made up these products failed to reduce risk, merely distributing it among different (but, more importantly, interconnected) shadow banking participants. At the height of the subprime boom, some dealers even issued “CDO-cubeds,” the riskiest protection repackaged into fresh securities to achieve the highest rating. The rest, as global finance soon discovered, was history.

Out of the ashes of what was then the greatest speculative bust on record arose a highly efficient shadow banking machine. After Lehman’s bankruptcy, the toxic markets of the subprime era — such as subprime synthetic CDOs — dried up, leaving only the shadow elements vital for channeling credit to the real economy. America’s shadow banking paradigm transformed to consist primarily of repos (repurchase agreements). Still, asset-backed securities (ABS) and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) have prevailed, with shadow banks — namely finance companies and other NBFIs (non-bank financial institutions), extending credit via shadow intermediation. The securitized loans, leases, and mortgages packaged into tradable instruments, meanwhile, have never been allowed to reach “CDO-cubed levels” of toxicity. Following another two drafts of the Basel Framework, regulators have contained extreme financial creativity — for now.

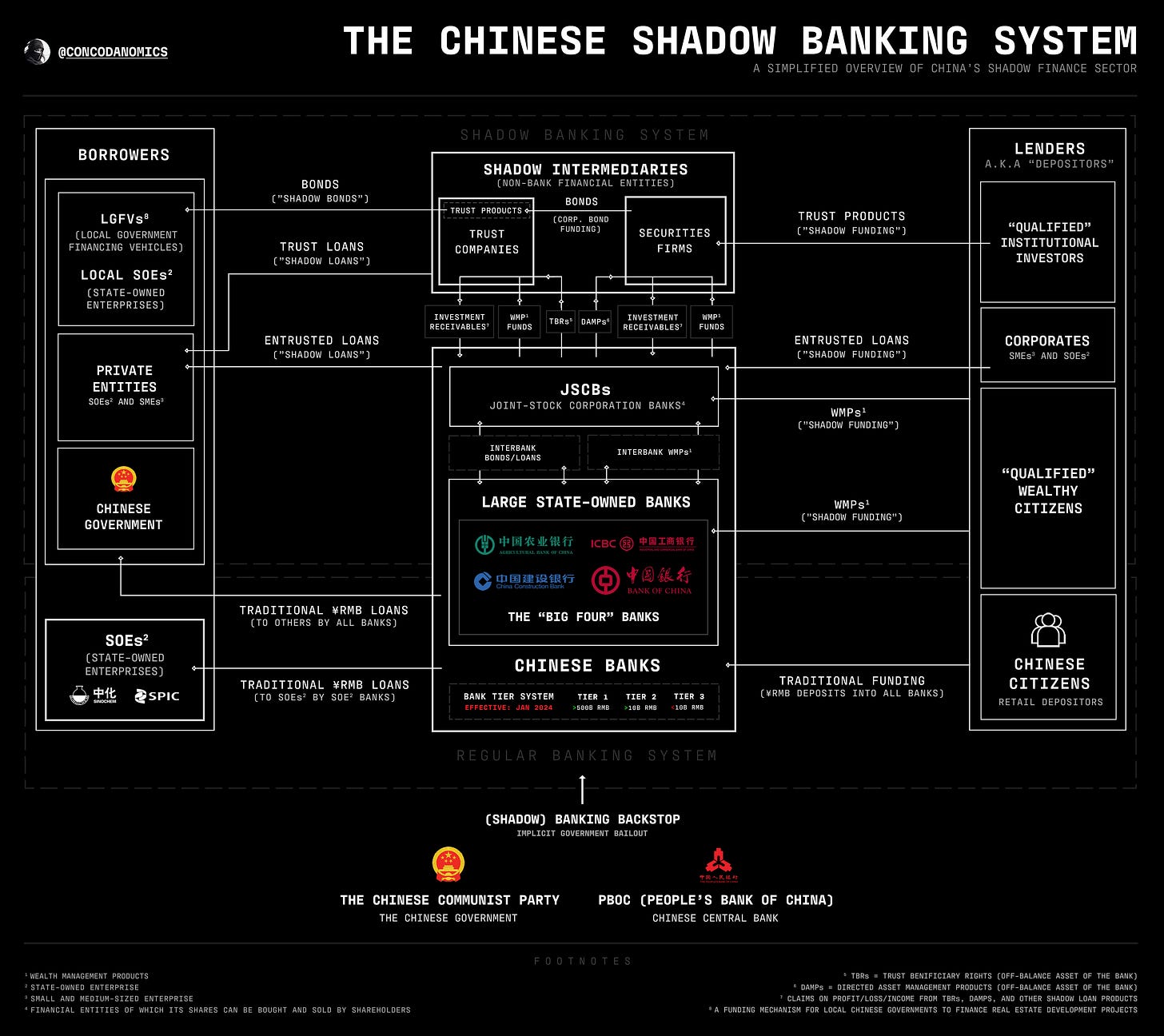

Meanwhile, across the globe, as America’s shadow banking sector had reached excessive levels of speculation and fallen back to Earth, another shadow system had achieved its peak and gradual decline: the Chinese shadow banking sector.

The backstory of how China’s shadow sector emerged is quite unlike America’s. The financial alchemy, actors, and instruments involved differ immensely. Yet, both systems have an overall similar flavor. Let’s dive in.