The Repo Market Exodus: Part II

an exodus from opaque repo markets could alter Treasury market liquidity

— to read part one of the repo market exodus, click here

The mass departure from the repo market’s shadowy yet most systemic regions has now commenced. Preparing to adapt to a centrally cleared era soon to be enforced by monetary officials, key market players have started fleeing the opaque markets for temporary cash loans secured against collateral, or “uncleared repos”1 for short. As most dealings in the U.S. Treasury market will require central clearing by mid-2026, participants who’ve been trading uncleared repos for decades have begun shifting operations to centrally cleared markets. Owned by the DTCC — an entity with a near monopoly on clearing and settlement2, the Government Securities Division (GSD) of the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC) remains the lone provider of centrally cleared repo trading. Subsequently, the clearing giant has started to absorb enormous inflows from uncleared repo markets, primarily trades that — without going through central clearing — will eventually be outlawed. With the latest figures revealing a ~30% rise in centrally-cleared Treasury trades since last year, the transition to a centrally-cleared era is already underway.

A vast cluster of obstacles, however, still await both monetary leaders and the most influential repo players impacted by a centrally cleared standard. Though it appears to be a simple vehicle for secured cash lending and borrowing, the repo market’s ultimate goal is to finance the highly leveraged positions of speculative players seeking to profit from perceived mispricings in Treasury securities, the same trades that glue U.S. sovereign debt markets together. Alongside a liquid secondary market — also known as the “cash” market, the world demands both a functional Treasury repo and futures market to deliver, among other things, ample liquidity. All three combine to enable efficient markets for U.S. Treasuries, thus producing relatively stable yields that serve as a benchmark for pricing trillions in dollar-denominated assets. Coincidentally, trades enabling such functionality also dominate volumes in uncleared repo markets, which face near extinction following the latest regulatory changes.

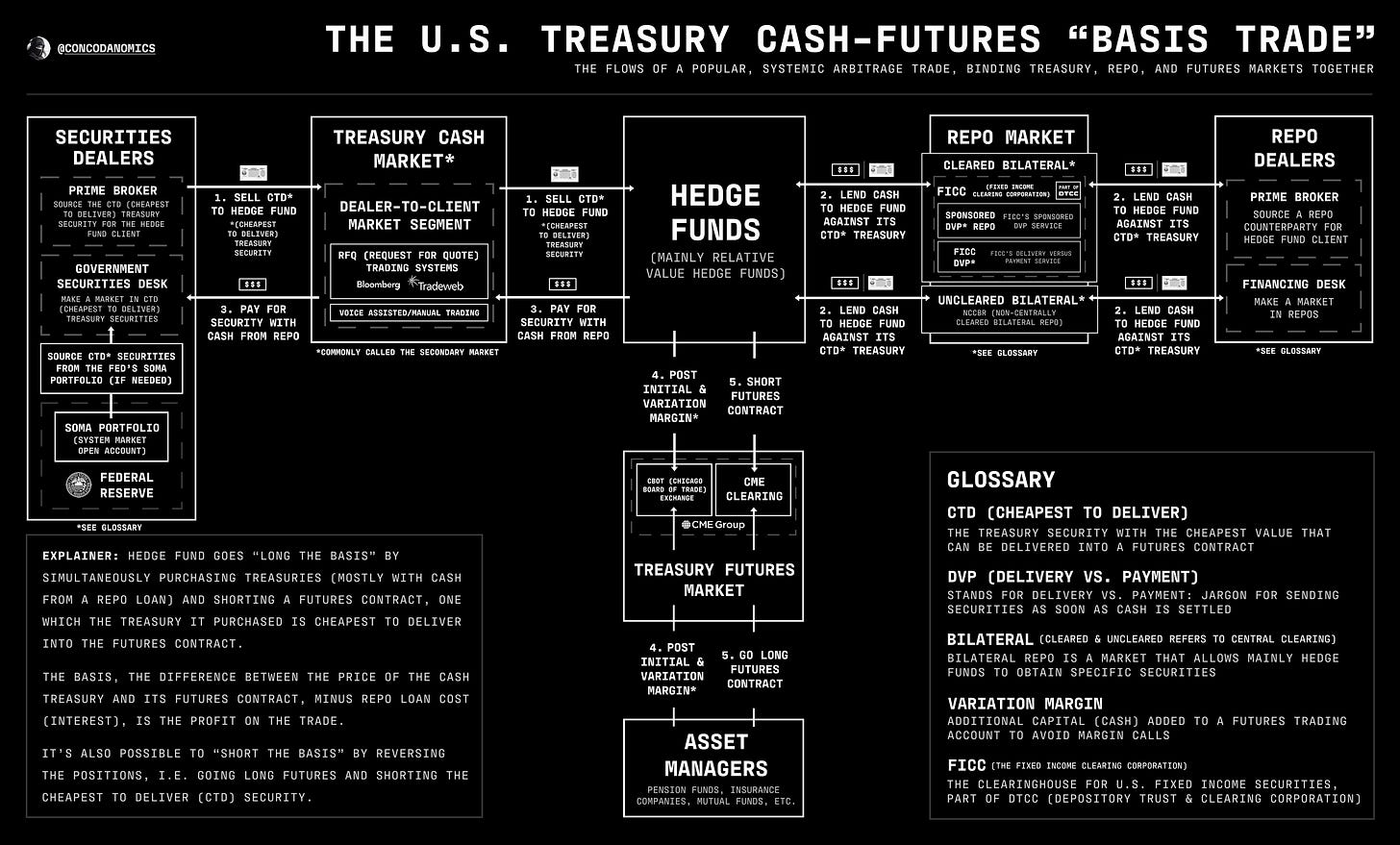

One of the most influential is the Treasury cash-futures basis trade, the primary mechanism for removing dislocations between prices of Treasury securities and their associated futures contracts. Somewhat unintentionally, this supplies unrivaled liquidity to the Treasury cash, futures, and repo markets. As futures prices detach significantly from their underlying securities in the cash market, hedge funds and other leveraged players step in to close the gap. When a Treasury grows cheaper than its futures contract, market participants will go “long the basis”: buying the cheaper Treasury security and shorting the expensive futures contract to profit from a spread upon delivering the Treasury into the futures market3. Eventually, enough players encountering the same opportunity push prices back into balance. But as these dislocations remain tiny, traders require significant leverage to justify entering basis trades in order to make a worthwhile profit. Thus, to eliminate such mispricings, hedge funds must access the uncleared repo markets to borrow cash and securities far exceeding their available cash on hand.

Alongside basis trades, hedge funds also speculate on mispricings between two similar Treasury securities, known as relative value (RV) trading, which produces trillions of dollars in speculative activity in uncleared repo markets. Although RV trades usually revolve around particular events, such as a Treasury auction, relative value trading could involve any two securities from which hedge funds believe they could profit and dealers are willing to make a market. A popular instance revolves around Treasury reopenings, where the U.S. Treasury issues additional amounts of a previously issued security (such as a 10-year note) one and two months after its initial offering. As a Treasury security issued in a reopening remains “on-the-run,” i.e., the most recently issued of a particular maturity, the associated increase in demand causes its price to outperform older, “off-the-run” securities for a few weeks after the auction. Hedge funds profit from this price appreciation by borrowing an out-of-demand (i.e. off-the-run) security, shorting it in the cash market, and using the proceeds it receives from the short sale to buy the in-demand (i.e. on-the-run) security. In the process, the hedge fund has entered a long and short position in two similar Treasuries, expecting to profit from the on-the-run security outperforming the off-the-run security over a bi-weekly period.

Like the cash-futures basis trade, hedge funds require immense leverage on their RV trades, generated through repos, to achieve worthy profits. They must turn to the Fed’s primary dealers and other larger dealers, who finance the hedge fund’s leveraged long and short positions by lending cash and securities via repos, while charging a fee to facilitate these transactions. As they effectively take the other side of hedge funds’ positions, dealers will likely hedge their exposures through derivatives markets or by taking the other side of the trade with another customer.

But for dealers to provide significant leverage, they must operate in the murkier uncleared parts of repo, free from rules and protocols that restrict elevated risk-taking. The greater the leverage, the greater the exposure hedge funds can achieve to engage in arbitrage trades that create efficient markets. Regardless, with the centrally cleared era looming, monetary leaders will have outlawed virtually all uncleared repo activity of leveraged players. Remove that privilege, in exchange for less systemic risk, and the market reduces its ability to remove mispricings in the world’s most systemically important debt market. What does this look like in practice, and what will be the resolution? It’s time to go deeper into the plumbing.