The Central Bank "Pledgening"

Wall Street and the Fed are about to grow more interlinked

Over a year after a systemic panic wiped out the riskiest banks on the planet, the Federal Reserve has completed the phase-out of its BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program) facility, seemingly without upset. The mini-banking crisis averted by its creation has exposed the regulatory establishment's decadeslong effort to thwart systemic risk as defective. But rather than accepting defeat, monetary leaders are about to double down on averting bank runs, not just in the U.S. but globally. The Central Bank “Pledgening” is about to begin.

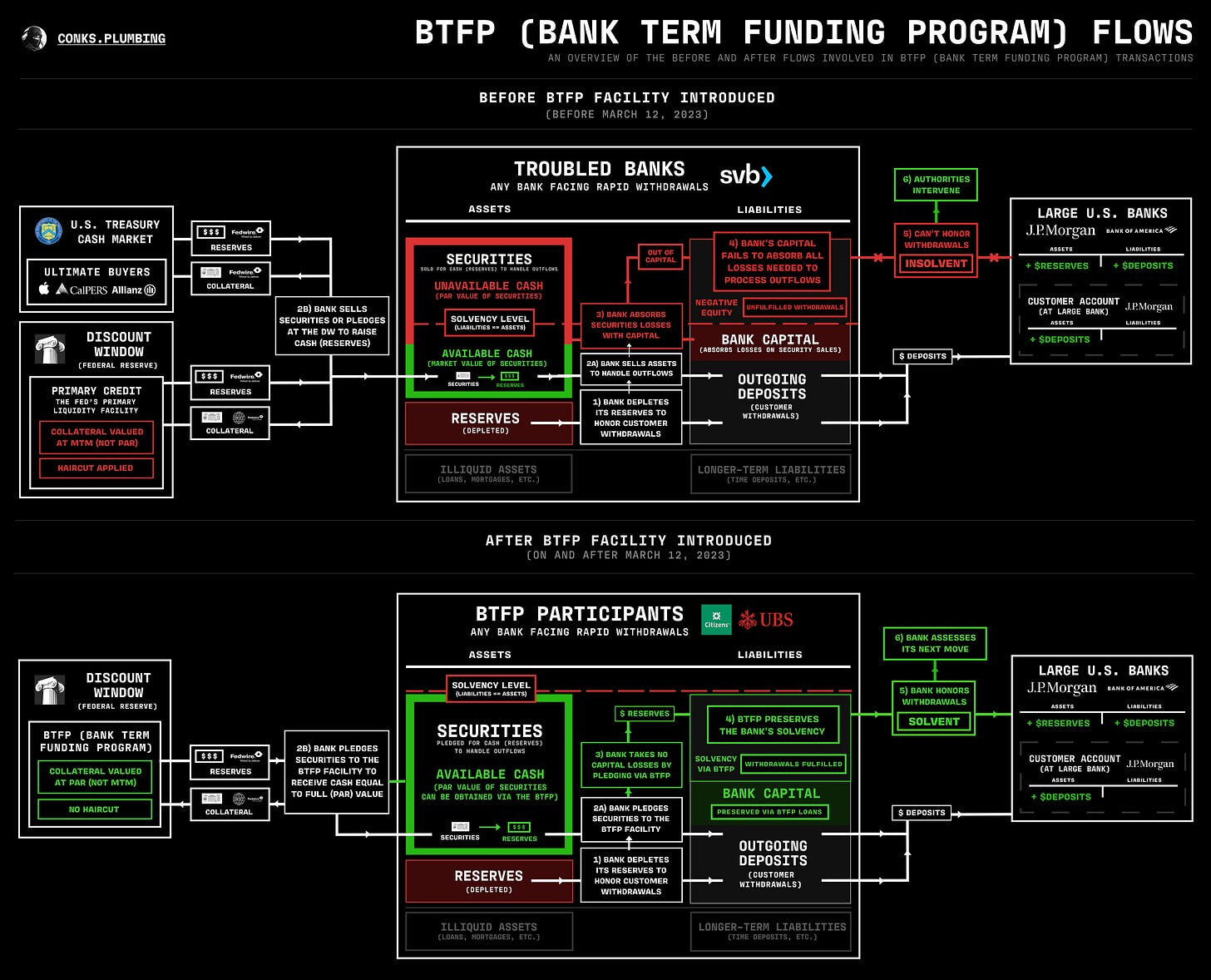

The epic run on Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in March 2023 prompted the downfall of the world’s most feeble banking corporations, from the notorious Credit Suisse to the SVB franchise itself. Yet a swift rescue of the U.S. regional — and ultimately global — banking system has diverted attention away from those who induced the SVB calamity. Only upon the fintech giant’s destruction have monetary officials turned instead to focus on the now-apparent defects in the Discount Window: the U.S. central bank’s official mechanism for preventing systemic crises. Following months of planning and indecision, Fed officials will soon unveil a revamped version of their “primary” defensive weapon.

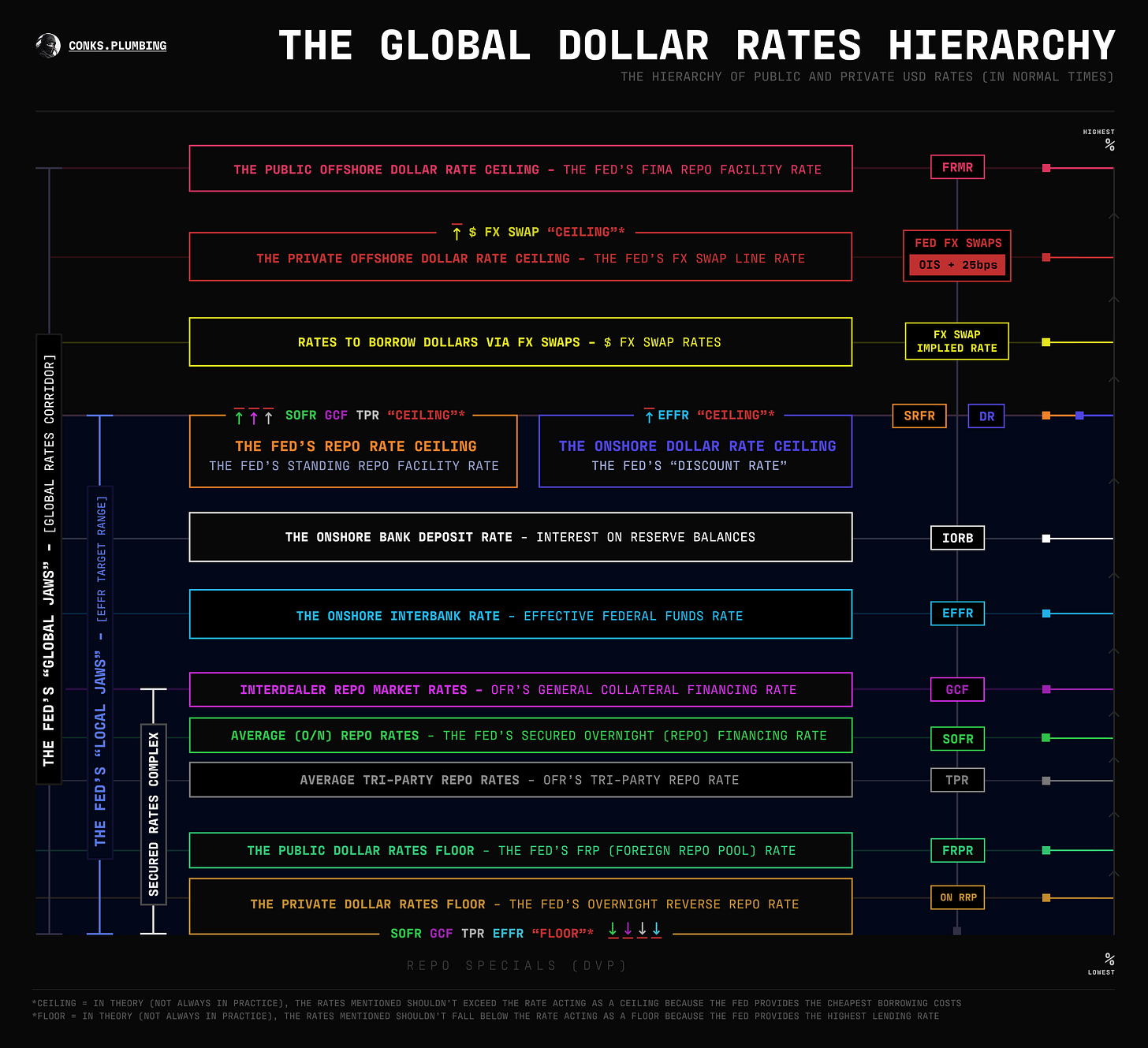

Acting as an onshore ceiling within the Fed’s global dollar rates hierarchy, the Discount Window has enabled the U.S. central bank to deliver endless liquidity to America’s banking colossus, all while deterring its benchmark interest rate, Federal Funds (EFFR), i.e. the interbank market rate to borrow reserves, from breaching officials’ target boundaries. Though imperfect, the Discount Window has averted most interbank squeezes by supplying reserves via numerous facilities, each with differing terms of entry. The most prominent and accessible by far, however, remains the Primary Credit Facility, or PCF for short. Serving as the Fed’s official rescue mechanism, the PCF provides almost all Discount Window loans to ostensibly sound banks desperate for reserves, which they use to try to stay in business during fierce outflows. The PCF relieves the pressure of heavy withdrawals, where too many depositors transfer their cash to other banks, usually in times of turmoil. Instead of “firesaling” assets (selling securities at a loss) to raise the reserves needed to process outflows, solvent yet illiquid banks can pledge virtually any triple-A rated asset to the U.S. central bank — from Treasuries to foreign currency bonds to CDOs — in exchange for emergency dollars.

Central bank access, though, comes at a price. To discourage overuse and stimulate private sector activity, the Fed charges borrowers a penalty rate for tapping the PCF, dubbed the “discount rate”. Its name originates from how the PCF acts as the Discount Window’s major “lender of last resort” facility, not from its cost of borrowing, which the Fed sets at a premium to private rates — not at a discount as its name suggests. Fixing the discount rate significantly above the Fed Funds rate should prompt banks to tap the Fed’s emergency facility only if a liquidity squeeze emerges. As their cost to borrow in the Fed Funds market surpasses the PCF, Fed liquidity becomes the cheapest alternative until interbank rates fall back into balance. Subsequently, the Fed setting the discount rate to equal the upper bound of its target range enforces a maximum rate for well-capitalized banks to obtain reserves. At least, in normal times.

In times of turmoil, however, as numerous episodes have demonstrated, banks aren’t always willing to borrow from the Fed’s official lender-of-last-resort mechanism. Facing the stigma of appearing troubled to their counterparties, banks have retreated from tapping the PCF even when it’s cheaper, causing rates to blow through the Fed’s acceptable upper limits. Crises such as the GFC (Great Financial Crisis of 2008) and the 2019 “repocalypse” instead revealed that increased intervention was the true lender of last resort (and the true ceiling on interbank rates), with the Fed inventing a myriad of facilities just to convince banks to access emergency funding. The recent creation (and following expiration) of the Fed’s BTFP was the latest reminder that central bank alchemy has remained the silent but genuine dollar backstop. Even so, the Discount Window’s PCF has preserved its handle as the Fed’s official lender of last resort (LoLR) mechanism.

Sixteen years after the GFC, the financial system has transitioned to a “secured standard,” where banks operate as utilities and shadow banks absorb most of the risk, knowing monetary authorities likely have their back in a crisis. The SVB banking panic has merely ushered in the next iteration of the secured standard, with fortifying central bank mechanisms being one of many new regulatory objectives. In the past few months, monetary leaders have hinted at their proposed modifications to the Discount Window, which ironically have been designed to prevent increased intervention. Yet this will also spur more interlinkage between the Fed and Wall Street via a “great pledge” of collateral. What does this mean in practice? Let’s unveil the mechanics.